With the advent of new technologies in armament production, a range of new-generation weapons which can travel more than Mach 5 is giving a new thrill to militaries around the world as their enemies can be decimated within hours.

Hypersonic weapons are becoming future of warfare due to high speed trajectory and kinetic racing towards a target with the press of a mere button.

In fact, hitting a target with a missile anywhere in the world in less than an hour is the US Pentagon’s goal with its ongoing development of hypersonic weapons.

Moving from the experimental phase to construction and deployment, however, is still a ways off. But recent activity on this front by the Chinese military may help speed things along.

China surprised many in the defence community in January when it tested a related device that can detach from a ballistic missile and be steered toward its target.

The US is conducting its own tests of various systems under development by the Defense Department, all of which would be capable of delivering conventional or nuclear weapons at speeds of Mach 5 or faster, so at least five times the speed of sound.

Last year, the Pentagon saw improvement in a trial run of a hypersonic device known as a scramjet that was attached to a B-52 bomber.

Spending on the scramjet technology for the B-52 had a cost of about $250 million from 2004 through 2011. Last year the Pentagon estimated that its Advanced Hypersonic Weapon program would cost about $600 million over the next five years.

The programs have been more than a decade in the making. The Defense Department first identified the capability as one of its missions in 2003.

Precision strike

The Pentagon says these types of weapons will be ideal for hitting mobile military units or terrorist groups that do not stay in one place for more than a day at a time.

Using existing weaponry would take days to hit those targets, according to the US Defense Department, because it would require getting forces into position before launching an attack.

And because the delivery systems for hypersonics are capable of delivering conventional weapons instead of nuclear warheads, the missiles offer more precision.

Critics of the program point out that because the missiles are very similar to those used for nuclear weapons, adversaries would not be able to tell the difference, leading some to erroneously suspect they are coming under nuclear attack. For countries with nuclear capabilities, that could lead to a counter-attack.

“These systems cause real escalatory risks,” said James Acton, a senior associate in the Nuclear Policy Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. But that is not his primary concern. He questions whether hypersonics are even necessary.

“A lot of this is being driven by technology at the moment, and not by strategy,” he said, noting that the scenarios in which these missiles would be used rely too heavily on intelligence that needs to be rock solid. During that period of intelligence-gathering, he said, existing means of attack could be put into position.

Funding for development of the Conventional Prompt Global Strike program increased from $174.8 million in 2012 to $200 million in fiscal 2013, even though the Pentagon only requested $110.4 million last year, according to a Congressional Research Service report.

However, NASA defines the hypersonic regime as speeds greater than Mach 5 but less than Mach 25. It further divides this speed regime into two parts.

One is the ‘high-hypersonic’ speed range between Mach 10 and Mach 25. The other is the range between Mach 5 and Mach 10 referred to simply as the hypersonic speed range (this is about 5300 to 10,600 km/h).

The latter is the speed regime where most of the recent discussion of hypersonic weapons has been focused.

Ballistic missiles with ranges between about 300 and 1000 km travel in this speed range, but they generally do not travel long distances through the atmosphere at these speeds.

Usually when hypersonic weapons are discussed people are referring to machines that can sustain flight in the Mach 5 to 10 speed range for a significant distance and period of time measured in minutes. For perspective, the Concorde supersonic transport cruised at Mach 2.

Press reports indicate there are only three nations with hypersonic weapons programs: the US, Russia and China.

In November 2011 the US Army conducted a successful test of the Advanced Hypersonic Weapon (AHW) demonstrator.

Glide vehicles

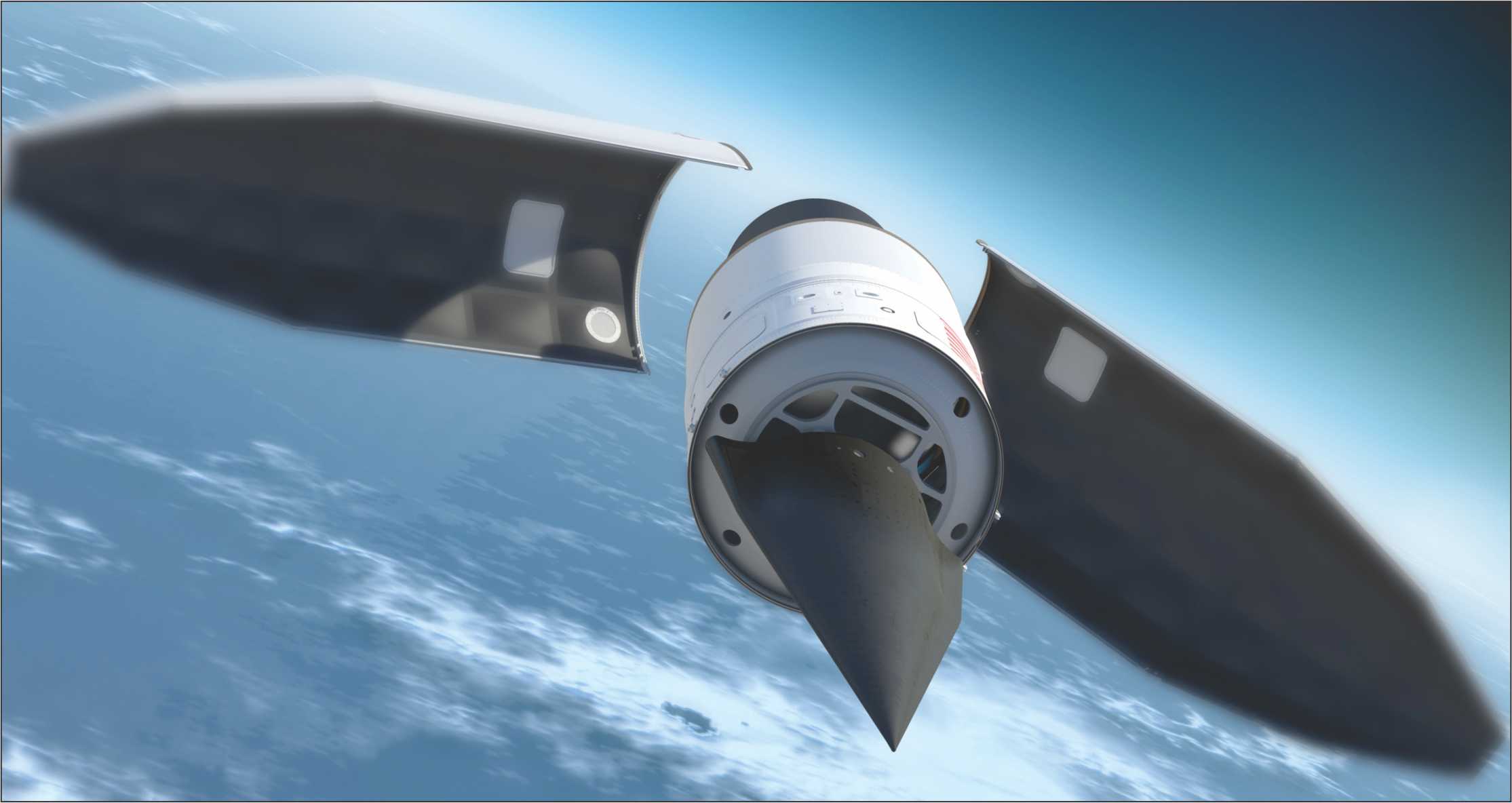

This is a hypersonic glide vehicle similar in concept to the reported Chinese system. A hypersonic glide vehicle couples the high speeds of ballistic missiles with the maneuverability of an aircraft.

The goal of the AHW test was to collect data on hypersonic glide vehicle technologies to inform possible future designs.

The test used a three-stage missile booster system to power the test vehicle to hypersonic speed and evaluated its performance on a flight over the Pacific Ocean.

A second US approach to hypersonic weapons made a similar advance on 1 May 2013 when the US successfully tested the Boeing X-51 hypersonic research vehicle.

It is powered by a supersonic combustion ramjet or ‘scramjet’ engine and flew about 306 km in three and a half minutes at just over Mach 5.

This was the first successful test of a scramjet-powered vehicle. The scramjet is efficient at hypersonic speeds, but as the name implies, the air flowing through the engine is traveling at supersonic speed, so the fuel must be precisely measured, injected into the air flow and ignited with extreme speed.

These successful tests indicate the US is well along the path to solving many of the problems associated with sustained hypersonic flight. These include the high drag and temperatures generated by vehicles traveling at hypersonic speed and developing an efficient power plant.

However, not much is really known publicly about the Chinese program. What has been reported indicates that their initial investments might be focused on building vehicles that can replace the re-entry vehicles usually carried by ballistic missiles.

These ‘hypersonic glide vehicles’, as the name implies, are carried by ballistic missiles, but once they descend into the upper atmosphere, their shape gives them much greater range and maneuverability than ‘normal’ cone-shaped re-entry vehicles.

So, based on various reports, the Chinese AHW programs might be characterised as working to improve the capabilities of ballistic missiles while the X-51 program is focused on making weapons that behave more like very fast cruise missiles.

For several years, new research for such a weapon has been going on. China and the US have both conducted tests of new hypersonic weapons systems over the past month.

Although both tests were unsuccessful, they signal continuing military competition between the two countries, which are each attempting to develop high-accuracy projectiles that can travel several times faster than the speed of sound.

On August 7, China performed an unsuccessful second test of its WU-14 hypersonic glide vehicle. The US in turn tested its AHW from the Kodiak Launch Complex in Alaska on August 25. The US test also failed.

Hypersonic weapons can hit their targets extremely quickly and effectively. If ever made operable, these weapons would be able to travel more than five times faster than the speed of sound and cover a range of several thousand miles.

Although this phase of the hypersonic arms race between China and the US is fairly recent, the weapons themselves have existed in some form for decades.

Hypersonic weapons are not that new ballistic missiles are hypersonic weapons.

However, the weapons that the US and China are now testing belong to a different class of hypersonic weaponry called boost-glide weapons.

Boost-glide weapons

Boost-glide weapons are launched by big rockets just like a ballistic missile is but then rather than arcing higher than the atmosphere, they are put on a trajectory to reenter the atmosphere as quickly as possible. Then they just glide to the target.

Boost-glide weapons are capable of traveling on a trajectory that makes them difficult for missile-defense systems to intercept.

These systems are designed to work against the high arc of traditional ballistic missiles. Boost-glide projectiles travel quickly and at a flat angle, working at speeds and trajectories that flummox existing missile defence technologies.

Prior to the most recent failed launches by China and the US, both nations had successfully carried out test-runs of their boost-glide systems.

When China tested its WU-14, it served as a sign of China moving towards longer range, stronger retaliatory and potentially preemptive capability.

The US’ concern is that China may eventually use its boost-glide weapons as nuclear delivery system. This could give China hypothetical nuclear first-strike capability across large portions of the globe, assuming that the US does not develop this capability as well.

In 2011, American scientists had successfully test-fired the Advanced Hypersonic Weapon. During that test, the AHW flew 2,300 miles in less than half an hour.

The cause for the most recent failure of the AHW in Alaska is uncertain, and the damage at the launch facility was apparently extensive.

For years, US Congress has been giving funding for US Army’s rapid development of the cutting-edge boost-glide Advanced Hypersonic Weapon (AHW) missile program.

Capable of flying faster than Mach 5 and penetrating enemy defenses, AHW augurs the Army’s re-introduction of a potent and necessary capability into its arsenal: intermediate-range offensive fires.

The United States’ boost-glide development program does in fact have a clearly defined development objective, and will not start an arms race with China-if anything it is a response to Chinese militarization.

Indeed, by swiftly introducing intermediate-range missiles such as theAdvanced Hypersonic Weapon in a manner similar to the ”Double-Track Decision” taken by NATO during the Cold War, the United States can encourage the global elimination of destabilizing intermediate-range missiles, while ensuring its ability to field them rapidly to enhance deterrence if necessary.

With the ratification of the Intermediate Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty in 1988, the United States and the Soviet Union eliminated nuclear and conventional ground-launched ballistic and cruise missiles with ranges between 500-5,500 kilometers.

The INF Treaty increased strategic stability (by eliminating a potent class of weapons that encouraged swift retaliation) and contributed to a peaceful resolution of the Cold War.

Since then, China has developed the largest, most active, and diverse ballistic missile program in the world, building hundreds of the destabilizing and escalatory intermediate-range weapons and aiming them at the United States and its allies.

Regional threat

These missiles have contributed to China’s growing anti-access, area denial (A2/AD) capabilities which seek to prevent US forces from operating in the Western Pacific, and threaten to upset regional peace and stability.

Specifically, China poses a major and growing threat to US joint operational access in the Asia-Pacific region. Traditionally, the United States has heavily relied on airpower in its power projection and strike concepts of operation.

Airpower, however, is increasingly challenged by the dual threats of structured attacks with offensive missiles and of advanced integrated air and missile defense systems (IAMDS).

Consequently, threats against airpower in the First Island Chain (and increasingly the Second Island Chain) are resulting in a greatly decreased potential force gradient.

China may be able to effectively target US or allied airbases and defend against the limited numbers of aircraft generated.

Additionally, long-range US munitions (such as cruise missiles launched from air or naval platforms) would face mounting difficulty penetrating China’s IAMDS, due to effective defensive sensors, weapons, and networks.

The Army can play a leading role in addressing the “conventional strike gap” by developing boost-glide intermediate-range missiles.

Boost-glide weapons would excel at penetrating dense IAMDS where aircraft would have difficulty operating.

Additionally, if they were mobile and practiced passive defense measures, they would provide the Joint Force with a potentially more resilient means of attack than tactical aviation, which is vulnerable to airbase targeting.

On the whole, boost-glide weapons would effectively contribute to the Joint Force’s efforts to counter Chinese A2/AD systems and diminish Chinese confidence in their ability to coerce other countries and wage war.

At the strategic level, boost-glide systems (and other intermediate-range missile systems) may contribute to a cost-imposing strategy against China.

By deploying relatively inexpensive offensive weapons such as boost-glide systems, the United States may asymmetrically drive China to invest in more expensive IAMDS, especially those capable of intercepting hypersonic missiles, instead of offensive, power-projection capabilities.

Therefore, US boost-glide development is oriented toward clear objectives, and research into hypersonics more broadly should be properly interpreted as a response to China’s rapidly advancing military capabilities, including its massive arsenal of intermediate-range missiles.

However, there are at least three reasons why this assumption on nuclear escalation is likely incorrect.

First, China has a highly secure second-strike nuclear force that boost-glide weapons would be highly challenged to seriously degrade-even if the United States explicitly proceeded to deliberately and systematically target Chinese nuclear forces (another unlikely assumption).

Second, it is against Chinese nuclear doctrine to launch on warning; accordingly, China has designed its forces to be able to withstand a nuclear salvo before successfully counterattacking.

Most importantly, though, it is unlikely China would use nuclear weapons in response to US conventional capabilities, such as boost-glide weapons, because China will become socialized to the US weapon systems.